Guess what! Some Muslims are in the news again. And as always, they are doing exactly the opposite of what their faith and values intended.

Guess what! Some Muslims are in the news again. And as always, they are doing exactly the opposite of what their faith and values intended.

And if you thought a minority of hysterical Muslims were slow (6 months) in responding to the Danish cartoons, try this for size. The Afghan authorities and judiciary took a whole 16 years to work out one of their own had changed religions.

The good news is that the Muslim government involved is, at least for now, from the good side. And thankfully, they seem to be doing something to stop the clear abuse of sharia law.

Freedom & democracy from Guantanamo to Kabul

Hardly a few weeks after the Danish cartoon saga, the pro-American government of Hamid Karzai has been caught out trying to revive the old Taliban legacy. And boy, don’t the war-on-terror brigade have egg on their faces.

Even poor Australian Prime Minister John Howard has admitted he isn’t very happy with the decision by the Afghan judiciary, whose judges are handpicked by Mr Karzai and his Ministers, to place a man on trial for the nasty deadly crime of … wait for it … converting to Christianity!

Australia’s troop presence in Afghanistan has recently been beefed up. Young Australian men and women are risking their lives to ensure that a pro-democracy and pro-freedom government can remain in power for long enough to potentially send a Christian to the gallows. Or was that the firing squad? Who knows?

Mr Howard says that when he first read about the Afghan Christian’s plight, he “felt sick – literally”.

But then, the Aussie PM shouldn’t complain. Poor Abdul Rahman has at least been told what he is charged with. Unlike so many of the Afghan and other Guantanamo Bay inmates who have been in custody for over 4 years now without charge.

Australia has one remaining Guantanamo prisoner. David Hicks faces what his US Military lawyer appropriately describes as a “kangaroo court”. Yet the Australian government refuses to lift a finger to assist one of their own citizens. With British PM Tony Blair visiting Australia, perhaps Mr Howard could learn some lessons from Mr Blair about how a country following the Westminster tradition of Parliamentary democracy should stand up for its citizens.

Misusing sharia to deny custody to a father

Still, this article is not about David Hicks or Guantanamo. Nor is it about the Abu Ghraib prisoners. This is about the Afghan government which practises the same excesses to those who claim that dropping depleted uranium on entire towns and cities is the best way to spread freedom and democracy.

And worse still, it is about people imposing barbaric punishments in the name of enforcing Islamic law.

Now before we start with the legal analysis, let’s try and master the facts. With all the hysteria of much western reporting, it is hard to know exactly what poor Abdul Rahman’s background is.

Now before we start with the legal analysis, let’s try and master the facts. With all the hysteria of much western reporting, it is hard to know exactly what poor Abdul Rahman’s background is.

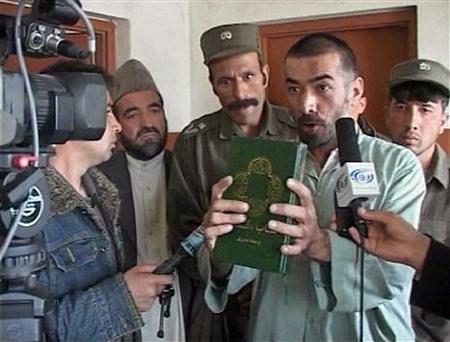

Abdul Rahman is a 41 year old Afghan father who has lived overseas for some 15 years. He returns to Afghanistan for a custody battle with his wife who lives in Afghanistan. A relative with a personal vendetta claims the father has converted to Christianity and dobs him into the authorities.

It’s amazing what people are prepared to do to pursue personal vendettas. Even if it is true that the father had converted to Christianity, what does this have to do with the price of Persian rugs in the Kabul bazaar?

The children have apparently lived in an Afghan Muslim environment all their lives. How they survived Russian intervention followed by civil war followed by Taliban rule followed US-led bombings followed the present chaos is anyone’s guess.

What are the merits of Rahman’s custody battle? Who knows. Certainly under the family law of most Western countries, he would have little chance of gaining custody. Under Australia’s Family Law Act, a court would be most reluctant to change the status quo of the children’s living arrangements without good reason.

And under Australia’s mandatory detention laws, the fact that the children are escaping a regime which kills them for belonging to the wrong tribe and/or sect isn’t enough to stop them from being thrown into a detention centre in the middle of the desert. At least that was the case until recently.

Indeed, one Kashmiri convert to Christianity was kept in Australian detention longer than any Muslim detainee and suffered severe trauma as a result. Peter Qasim’s conversion and fears for his safety didn’t stop the Howard government from keeping this hapless fellow behind bars.

To hudood or not to hudood

Even more hypocritical and scandalous than the Australian government’s alleged commitment to freedom for Christian converts is the Afghan judiciary’s commitment to sharia.

According to trial judge Ansarullah Mawlafizada:

The Prophet Muhammad has said several times that those who convert from Islam should be killed if they refuse to come back.It seems the learned judge has not read the verse of the Qur’an immediately following the Ayat al-Kursi (“Verse of the Throne”). In verse 256 of Surah al-Baqarah, the One who created Sayyidina Muhammad and honoured him with the Seal of Prophethood declares:

Let there be no compulsion in religion.

There isn’t a huge amount of consensus among classical and modern sharia scholars on what acts constitute apostasy or what its punishment should be. Indeed, even scholars who agree that an apostate should be put to death place stringent conditions on this punishment.

According to Shaykh Nuh Keller’s translation of Ahmad ibn Naqib al-Masri’s classic work of Shafi law entitled Umdat as-Salik (“Reliance of the Traveller”), a condition for implementing the death penalty is that the caliph or his representative must ask the apostate to repent and return to Islam (see para o8.7 of the Revised Edition).

Further, only the caliph or his representative can carry out the punishment. Unless I am mistaken, I do not believe Hamid Karzai is regarded as the Caliph of Afghanistan. Chapter III of the Afghan Constitution sets out the powers and duties of the President, described there as the Head of State. Chapter IV sets out provisions relating to the Government. Nowhere do the words “caliph” or “caliphate” appear.

Further, Abdul Rahman is said to have converted to Christianity whilst living in the United States. Whether this gives the Afghan courts jurisdiction over his “offence” is unclear.

Various scholarly views of apostasy

Indonesia is the world’s largest Muslim-majority country. Its largest Islamic organisation (which is also the world’s largest) is the Nahdlatul Ulama (Council of Scholars). One of the most senior sharia scholars and lawyers in the NU is Professor Mohammad Fajrul Falaakh.

Professor Falaakh is Vice Dean for Academic Affairs at the prestigious Gadjah Mada University Law School in Yogyakarta where he teaches both undergraduate and graduate studies in government and public law. He is also a member of the National Law Commission of the Republic of Indonesia (2000-03), and Deputy Chairman of the Central Executive Board of NU. Apart from extensive studies in Indonesia and the UK, Professor Falaakh has also worked within the traditional pesentran system of religious training.

In 2002, Professor Falaakh visited Australia and New Zealand at the invitation of the Centre for Independent Studies. On 11 December 2002, he delivered the Acton lecture on Religion & Liberty at the Great Hall of the Parliament of New Zealand.

(An edited version of the text of Professor Falaakh’s talk can be found by accessing the website of the Centre for Independent Studies, going to the search feature and typing in the word “Islam”. Professor Falaakh’s speech is the first item in the list.)

In his speech, Falaakh lists the five basic principles of sharia. The first item in this list is “the protection of religious freedom, or the protection of religion and the way religion is observed”. Falaakh says that this freedom must be preserved even where sharia is “interpreted … more strictly”.

The third item in the list is "hifzh al-aql, meaning mine-that is, freedom of thought, freedom of conscience.” Here, Falaakh addresses the issue of apostasy directly, especially as applied in a pluralistic society. He continues …

What if, according to my own understanding, I exercise my freedom of thought and choose another religion, denouncing the one that I had professed before and embracing the new one? What about the regulation or provision that many Muslims believe in that those who renounce Islam will be punished by death?Falaakh is not alone in the view that the original capital punishment for sharia was more related to the crime of treason. Professor Abdullah Saeed of the University of Melbourne, a graduate of the International Islamic University of Madeenah Munawwarra, recently co-authored a book on the subject together with Hassan Saeed, Attorney General for the Maldives.

… The traditional, conventional understanding of apostasy in Islam says that once you enter into Islam there is no way that you can leave, otherwise you will put yourself to death. If that is really the case, why does the sharia claim early on that there is to be protection of religion?

… There was a time when some parts of the Muslim community back in the 7th century were reported to have had renounced Islam and they were chased and punished by death … at the same time, they also waged war, turning against the community they had previously belonged to. So was that a very obvious case of apostasy or a case of rebelling against a political entity that you used to agree with-in other words, violating a political pact you created together with other people? So perhaps it was not really religious at all. It was simply a political affair.

Entitled Freedom of Religion, Apostasy & Islam, the authors argue that the early development of the law of apostasy was largely a religio-political tool. Further, there is a diversity of opinion among early Muslims on the punishment. There are substantial ambiguities about what constitutes apostasy, and the textual evidence doesn’t always assist in resolving these.

The authors conclude that those arguing in favour of the death penalty neglect a vast amount of clear texts in the Qur’an which favour freedom of religion in constructing the law of apostasy.

Indeed, even if the criminal law of sharia regards apostasy as a serious enough act to warrant being classed as hudood (subject to capital punishment), can such punishment be implemented in an environment where government, judiciary and police are corrupt? Is the case of Abdul Rahman not one in which Professor Tariq Ramadan’s call for a moratorium on hudood punishments should apply?

Conclusion

Given the stated commitment of Afghanistan Constitution to international law as enshrined in the Principles of the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, perhaps the most appropriate Muslim response to the arrest and trial of Abdul Rahman is that of a spokesman for the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils.

When asked about Abdul Rahman, AFIC spokesman and lawyer Haset Sali responded:

Such barbaric action by anyone seeking to quote Islam as supporting their criminal action needs to be dealt with as a crime against humanity.One hopes other Muslim leaders take a similar position to what is clearly a travesty of sharia and of justice. If Muslim minorities do not stand up for the rights of non-Muslims in Muslim-majority states, their occasional claims to being oppressed minorities themselves will not be taken seriously.

Or as the Prophet Muhammad (peace & blessings of God be upon him) said:

The one who oppresses the non-Muslim citizen will have me testifying against him on the Day of Judgment.

(This article first appeared on the AltMuslim website.)